Japan Between 1868 and 1912 (The Meiji) Part I

The contacts with the Europeans had shown the country its material inferiority and the danger, by remaining isolated, of losing its independence. On the other hand, many of those previously opposed to the opening of it, had changed their minds, after hasty trips or studies abroad and now advocated the need to assimilate Western civilization in order to be able, if necessary, to fight the foreigner with weapons. the same. The nation set to work, led by men of sure intuition, who in half a century of work were able to raise Japan from the obscurity of isolation to the dignity of great power, making the Meiji the brightest era in the history of national progress..

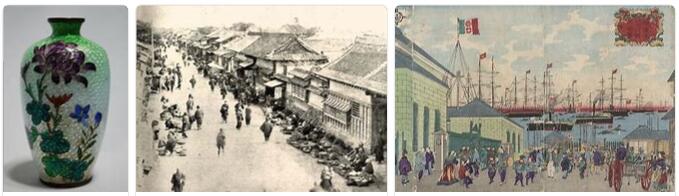

According to PICKTRUE, the first steps marked a great fervor of social and political reforms for which the country also required the collaboration of European and American specialists. The national reconstruction begins with a memorial, dated March 5, 1869, with which about fifty of the most powerful daimyō offer their fiefs, income and men to the emperor. Their example was immediately followed by others and on 7 August 1869 an imperial decree abolished the fiefdoms and constituted with the daimyō and the kuge the new nobility (kwazoku). But the work of centralizing power and unifying the national territory was hardly done when a series of internal and external events attracted the attention of the government. After the Restoration Japan had sent letters to the king of Korea informing him of the changes that had taken place; the response that came was full of insults that caused great resentment throughout the country, arousing in you the desire to wash away the shame suffered. While the question of a punitive expedition was being discussed, a mission led by Iwakura Tomomi, left (1871) for Europe and the United States with the aim of obtaining the revision of the treaties. Upon his return to his homeland (1873), having only received the advice to proceed with radical internal reforms before any proposed revision, the mission found the Council of State divided into two camps with regard to the behavior to be held towards Korea. Iwakura’s energetic attitude helped to thwart a Japanese intervention and, at the same time, the inevitable international complications, while the interventionist ministers (Saigō, Soejima, Itagaki and others) resigned. The nation, however, far from forgetting the Korean insult, was only waiting for the right moment to settle the bill, and the opportunity presented itself in 1875, when a strong Korean fired on a Japanese gunboat, sparking intense indignation in the country. A few years, on the other hand, had been enough to show Japan the danger deriving to its own safety from a Korea isolated from the world and, due to the long misrule, disorganized and powerless to defend itself, especially since the excellent ports of its southern coasts could not fail to be an irresistible lure, especially for Russia. Japan resolved, therefore, to take on the same task that the United States had taken on it, to draw Korea out of its isolation and take care of its westernization. A demonstration expedition, modeled on that of Perry, was set up and the command entrusted to General Kuroda. The operations had a quick and happy outcome: Korea had to surrender and the friendship treaty signed on February 26, 1876 marked the opening of another Asian nation to the world.

Meanwhile serious events were maturing inside, the origin of which is to be found in the disillusionment felt by some elements who had supported the emperor against the shōgun, in the belief of a return of Japan to pre-feudal times. The main exponent of these was Saigō Takamori (1827-1877), ex-samurai of the province of Satsuma, one of the ministers who resigned in the split of 1873, who, given that the purpose of the government was the complete westernization of the country and the abandonment of traditional customs and habits, he retired to Kagoshima, where he opened an arms school to which young people flocked. The government, aware of the danger, tried, in vain, to lure Saigō to itself. The inevitable conflict between the old and the new order of things broke out when, on January 10, 1877, the use of the two sabers was forbidden, the most expensive symbol of the samurai. The 30,000 insurgents commanded by Saigō were defeated, after 7 months of struggle, by the 76,000 imperial soldiers and Saigō himself perished there. Other minor riots were also quelled. The victory also served to show the country that the much-despised peasant, if properly trained, could be as good a soldier as the samurai.

For over a decade after these events, all of the government’s energy was spent on promoting industrial development and the prosperity of the nation. This period is characterized by an intense participation of the people in the political problems of the time, problems which, thanks to the spread of the press, had largely gained public attention. The most important event is the establishment of the constitutional regime.