Theater in Japan

The emergence of classic theater forms

Japan has a very old theater history, while the country is known for an exciting modern theater that has developed at the intersection of its own traditions and influences from the West. The oldest forms of theater are based on ritual-based forms of expression with dance, music and theatrical elements and were known as early as the 700s. After Buddhism was introduced in Japan, many impulses came from the Asian mainland, and some of these are probably the basis for developments in theater and dance. Mikagura was largely a musical and ceremonial play about the gods who may have absorbed original, folk elements. Religious puppet theater plays, satokagura, existed in connection with Japanese watch religions.

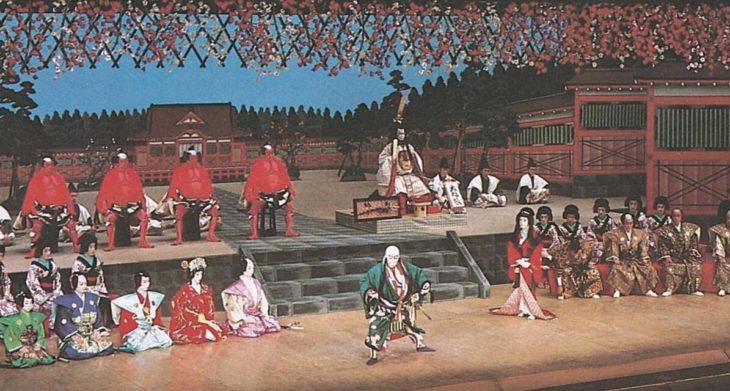

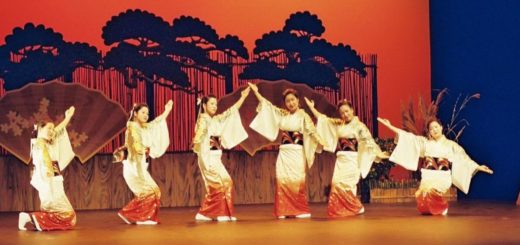

Gigaku was a regular scenic play from the Asian mainland that had evolved in the context of temple art and which in the 800s had its own Japanese design. It was probably a kind of dance theater game with masks and dramatic elements. The Bugaku game also came from the Asian mainland, and with its ceremonial dance elements survived at the Imperial Court up to our time. It was performed under the open sky and also had a strong nature of entertainment. From this, the classical Japanese theater forms no and kabuki evolved. Sarugaku game, which was another scenic form of expression with strong elements of dance, had its heyday from the mid-1000s to the mid-1200s. It was a very artistic and acrobatic form with elements of satire and irony, which had initially also used spoken dialogues.

From dance games such as sangaku and dengaku, forms of play such as sarugaku-no-nô and dengaku-no-nôu, ie precursors of the no-theater, evolved. Kyôgen form stood in the immediate context of the no theater, and it was the oldest developed speech theater tradition in Japan. It was based on figures and types, and is reminiscent of the European mime tradition from antiquity to commedia dell’arte. Bunraku was the name of a theater in Osaka, and in the 1600s it gave the name to a much older puppet theater tradition based on reality-designed puppets with eyes and eyebrows. The Kabuki Theater was based on popular pieces of equipment and was originally played by only female actors. However, in the 17th century, male actors took over, and it became commonplace for male actors to also play female roles. The classical theater forms in Japan, next to no and kabuki, were thus kyogen and banraku.

Modern Japanese Theater

In the late 1800s, works of European drama were first translated and played in Japan, such as plays by Shakespeare and Ibsen. At the same time, attempts were made to reform the classical Japanese theater forms by introducing shin-kabu-ki, the new kabuki, and shimpageki, the new school. The result of this was a commercial kabuki theater designed for pure entertainment, and which still exists. However, if one were to play a Western repertoire, one had to adapt to a Western theater style. Shingeki, the movement for a new theater, had such a development as its goal by initially imitating and adopting western theater forms, both in terms of acting and drama. This created little public interest.

The Tsukijigekijo theater building was erected in Tokyo in 1924 by a theater group that wanted to break with the imitation of Western theater, and became a representative of a non-commercial and partly political and proletarian ideal. This was downplayed by the fascist regime in Japan after 1931, and their active activities – which applied to the Shingeki movement at all – did not regain a level playing field until after World War II. A central representative of this movement so far had been the director and playwright Kaoru Osanai (1881-1928), who had worked on the Stanislavsky method. A large number of pieces from the European repertoire had been set up, and democracy as a movement had largely been the ideal for the business. This attitude was what the fascist regime could not endure.

Stable ensembles within the movement have been Bungaku-za, Mingei-za and Haiyu-za since the 1950s. Brecht eventually became a central playwright and a rich and internationally acclaimed Japanese playwright also developed. In general, there has been little support for theater operations in Japan, and the various companies have had to manage with few funds. In the last ten years, attempts have been made to soften the classical forms of theater, and to some extent let the classical and the western inspired influence one another. A very special variation of this development is represented by the so-called Japanese avant-garde theater.

Avant-garde theater since the mid-1960s

This development must be seen in the light of the influence of German expressionism as early as the 1920s. In Japanese, the avant-garde movement was called angura, linguistically a kind of counterpart to the English underground. The Angura movement has seen itself as a counterpart to shingeki with its partly naturalistic theater ideal, with an emphasis on intuition and feeling. Angura has relied on expressiveness and stylization and mixing of the media. It has probably drawn some inspiration from Western avant-garde movements in the 1970s and 1980s. One of the goals of the Angura movement has been to realize the ideal of unraveling the distinction between the audience and actors, an ideal derived from European historical modernism.

Key names in the Japanese avant-garde theater since the 1960s have been Jûrô Kara, who founded Jôkyô Gekijô, Theater of the Situation, in 1964. The now deceased Terayama led the Tenjôsajiki group and the somewhat younger Suzuki founded in 1968 Waseda-Shôgekijo. Of playwrights may be mentioned Makoto Satô (b. 1943), who has worked with the cellar theater Jiyû Gekijô. “Center 68/71” is a newer group. Of the directors, Terayama is probably considered the most important from this time, with his strong inspiration from, among other things. Artaud and Dadaism. He also recorded elements of the classic Japanese theater forms. The second generation of the Angura movement includes Kôhei Tsuka (b. 1948) and Shôgo Kta (b. 1939), while an even younger generation is represented by Hikedi Noda (b. 1955). This picture also includes Butho dancers like Min Tanaka, who has also worked at the Black Box Theater in Oslo, and Carlotta Ikeda. Of recent pure theater groups can be mentioned Dumb Types who, through his work with the Danish project theater group Hotel Pro Forma, has also done a project in Norway. Stylization and violent grotesque instruments on the one hand, and more conceptual and technology-oriented on the other, characterize this development in Japan.