Japan Recent History

The Japanese trace their history back to the year 667 BC when the first Jimmu emperor, or Zimmu, conquered Japan, and set the capital in Casivabara.

However, this date must be postponed for 6 centuries. Until the sixth century, that is, the introduction of Buddhism from China, Japan lived isolated. Around 800 the capital was transferred to Kioto, around 1000 imperial power began to be severely limited by members of the military aristocracy, especially palace masters (Shogun, Thaycun); until, in 1867, the revolution broke out, the Tenni fully emancipated themselves from feudalism.

Meanwhile, Japan had gradually strengthened and enlarged. In the third century AD, letters, silk industry and others were imported from China.

According to Abbreviationfinder, an acronym site which also features history of Japan, in 1854 Japan entered into a commercial treaty with the United States and, in 1858, with Russia, Great Britain and France.

In 1867 that revolution broke out which concentrated all power in the hands of the tenor Mutsu-Hito (1866/1912), the reforming sovereign. From this moment Japan walked on the path of progress, and apparently Europeanized. His victories in the war against China (1894) brought him the Formosa islands, the Pescadores; those against Russia (1904/05) Port Arthur, Dairen, part of the island of Sakalin and the protectorate of Korea. After the war, Japan entered into an alliance treaty with Britain and systematically proceeded with reforms.

In December 1914 he declared, as an ally of Great Britain, war on Germany and in a few months of action he removed the protectorate of Kiao-Ciou in China. Then he sent an ultimatum to China, from which he had significant political and commercial concessions and a “mandate” on ex-Germanic possessions in Oceania, in 1920.

The son Yoshi-Hito was succeeded by the emperor Mutsu-Hito, under the regency, because he was ill, of the crown prince Hiro-Hito, who, upon his death, succeeded him in turn in 1926.

The Japanese people worked assiduously and prepared an expansion plan, made evident especially in the second half of 1931 with powerful land and sea armaments, which worried the European and American powers.

Japan acted directly in Asia, created the free state of “Manciù-cuo”, left the League of Nations and did not return the ex-Germanic territories received in the mandate. The Japanese government repudiated the name of Japan in the traditional form and restored the form of Japan, from the name of the main island (May 1934).

The natural disasters, which frequently ravaged the volcanic and earthquake-prone country, did not distract the Japanese empire from the expansion policy on the continent.

On January 22, 1935 Japan bought the ex-Chinese railway in Manchuria; on April 5 the emperor of Manchu-cuo visited his Japanese colleague in Tokyo, the first example of visits between heads of state that history remembers in the Far East. Other important events were: the ultimatum of 23 July in Mongolia and the occupation of some centers in the 5 northern provinces of China; the definitive exit from the League of Nations, the request for naval parity and the abandonment of the Naval Confederation of London.

The fortification of the Pacific islands, the project to cut the Isthmus of Crah (which connects the Malacca peninsula to Siam), the increase of forces in northern China, the alignment of the currency and the hourly unification with Manchu – they were symptoms of an organic plan of domination of the Far East and the western Pacific.

Significant was the “anti-communist pact” concluded with Germany on November 25, 1936 and the following year with Italy.

The aversion to British, French and American interventions to the Chinese campaign was accentuated and adherence to the politics of totalitarian states was accentuated. The Conference of Cernobbio, of 4 August 1939 between the ambassadors of Japan in Rome and Berlin, which followed the blocking of negotiations with the United Kingdom, and the denouncement of the trade treaty by the United States, showed a significant weakening of the British influences in the Far East.

After the Berlin-Moscow rapprochement, Japan insisted on asking the British and French armed forces to clear out the locations they were however manned. On August 24, Japan denounced the “Treaty of Nine Powers” and accelerated the timing of the conquest of China.

After World War II broke out, Japan aligned itself with the Axis and perfected the Tripartite.

Japan’s main interlocutor in this war was the United States. They declared hostilities open after the sudden Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on August 7, 1941. Much of the American fleet was destroyed by repeated Japanese airstrikes.

But the extraordinary military and economic power of the United States in a short time was able to bring into combat, especially in the Pacific, of privileged bodies, such as the “marines” who, mechanized to the maximum, but of a valiant temperament, inflicted severe defeats on the enemy,

Each Pacific island, occupied by the Japanese, was conquered and conquered with great human sacrifices and so much honor.

The war proved to be longer than expected, both for the preponderant means available to the antagonists and for the value of the fighters. And then, to close the interminable game, the United States carried out the first atomic bombing in history, that of Hiroshima on August 6, 1945; 66,000 people died, many thousands more were defaced and, in any case, contaminated by the atomic bomb. After only three days, on August 9, the city of Nagasaki suffered the same fate. Japan on its knees surrendered. The emperor asked his subjects for forgiveness for having caused them many mourning and pain.

After the catastrophe, Japan quickly tended to rise again, adapting to the needs of the new situation brought about in the Far East by the antagonism between the United States and the Soviet Union.

On May 3, 1947, Emperor Hiro Hito promulgated the new democratic Constitution to the Diet. Japan’s rehabilitation promises, repeatedly made and reconfirmed by Mc Arthur on the occasion of the 5th anniversary of the surrender (September 1, 1950), after a long series of diplomatic conversations between the United States representative, Foster Dulles, and those of the other powers interested in Japan’s return to normal, materialized on March 31, 1951 in a declaration by Foster Dulles himself in Los Angeles, which summarized the conditions of peace, established essentially by the United States without collaboration, indeed in full contrast with the Soviet Union. The peace treaty was then concluded at the San Francisco Conference (4-8 September) with delegates from 51 states including three (Soviet Union, Poland,

For it Japan renounced all rights over Korea, the Kuril islands, the Sakalin, Formosa, Pescadores, Antarctica and other minor territories. He pledged to repay war damages and inspire his future policy to that of the United Nations. On the same day, September 8, Japan entered into a military assistance pact with the United States.

On April 15, 1952, peace was signed with the United States in Washington and the end of the occupation set for 28.

At the same time, Japan entered into a mutual security pact with the Philippines, Australia and New Zealand.

Violent riots broke out on May 1st in Tokyo. A treaty of friendship with India was concluded on 9 June and a trade treaty with Indonesia on 7 August. The rearmament issue was discussed by the Pacific Conference in Honolulu on 4/6 August, between representatives of the United States, Australia and New Zealand.

In the elections of April and October 1953, the liberal party led by Prime Minister Yoshida prevailed.

But the conservatives disagreed with his policy. They wanted the country to be closer to the Soviet Union and normalize relations with popular China. They did not want to depend almost exclusively on the United States, so in 1954 they overthrew the government of Yoshida and replaced it with the democratic Hatoyama. Two years later a pact tied the country to the Soviet Union which renounced the reparation of war damages and undertook to admit Japan to the United Nations assembly. However, the Soviet Union was left with Sakalin, the Kurils and all the rights to Manchuria, lost in 1905. But it promised the return of the Habomai and Shikotan islands.

In subsequent years, under the governments of the liberal-conservatives Ishibashi, Kishi and Ikeda, a policy of economic expansion was developed towards the countries of Southeast Asia, Africa, Latin America and also with popular China.

On 18 December 1956 he entered the United Nations.

The elections of 1955 had been won by the liberal democrats and in 1958, albeit with a slight drop in votes, they were confirmed. The socialists in 1959, after various disputes, split into two main branches: socialists and social democrats.

In 1960 the socialists promoted anti-American demonstrations which, however, could not prevent the signing of a Japanese-American security treaty. They managed, however, to prevent the then US president Eisenhower from visiting Tokyo in June, and a month later N. Kishi resigned. He was replaced on July 14 by the liberal Democrat Hayato Ikeda.

On October 12, 1960 the socialist leader Inejiro Asanuma was assassinated.

The 1960s represented for Japan a great growth in economic well-being, so much so that it became the only industrialized country outside the western and socialist areas.

Three phenomena in this period contributed to transform Japan: urbanization, economic well-being and pressure from the mass media. The latter, acting on greater financial possibilities, pushed the population towards new ways of life.

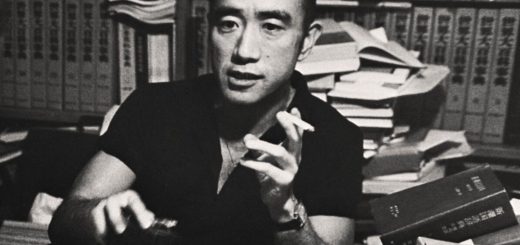

But the “Japanese miracle of economics and technology did not completely disappear the traditions of Japanese culture, which, however, had such a large decline that one of the most famous literary men of the country of that time, Y. Mishima, committed suicide.

The students, sensitive to the maintenance of their culture, refusing any form of modernized society, staged demonstrations that culminated with the occupation of the University of Tokyo in 1969. But, aware of not being able to achieve radical results with their disputes, they ran out of their attacks with terrorist actions that lasted until almost the mid-70s.

In domestic politics there was a lot of stability, certainly due to economic well-being. In spite of this, the Communist Party, at first small, was growing; his followers were mainly elements of the urban middle class.

With Yoshida’s death in 1967, stability was shaken. His successor, E. Satò, with an incisive personality and great maneuvering ability, brought the country back on the tracks of greatest productivity, so much so that in 1970 the goal of doubling the national gross product was reached. And Japan, under its long government, became the third world power.

Throughout the 1970s Satò, with his sagacity and his political ability, not only domesticated the student protests inside, but in foreign politics he achieved remarkable successes. The United States, after prolonging the mutual security treaty, returned the islands of Okinawa and the Ogasawara Archipelago to Japan. He also obtained to be able to adhere to the “non-proliferation” treaty.

Important events occurred at that time: Hiro Hito, emperor of Japan, was the first to visit Europe and Nixon, president of the United States, recognized popular China. The latter fact put Japan in crisis which was forced to change its policy with Taiwan. This constituted a check for Satò who, continuing his hostility towards the Beijing regime, was forced to resign.

His successor, K. Tanaka, solved the problem by going to Beijing. Then, at the beginning of the 1973 world energy crisis, the Japanese economy suffered a severe blow; the opposition took the opportunity to accuse Tanaka of having achieved his personal wealth by illicit means, and forced him to resign. But not before he received American President Ford in 1974, the first to visit Japan.

The new premier T. Miki, in December 1974, tried to contain inflation and brought the country back to stability. In 1975, in addition to the commitment to strengthen relations with China, Miki also made a trip to Washington where he reaffirmed his friendship with the United States which, in turn, renewed the commitment to work for the defense of South Korea,

In 1976, ex-Prime Minister Tanaka was involved in the Lockeed scandal and he was forced to resign from the party and the December elections took away the absolute majority from the Liberal Democratic Party.

This situation led Miki to resign. He was replaced by T. Fukuda. However, the 1977 elections yielded modest results for the ruling party. Fukuda, in turn, in 1978 retired from office to give way to M. Ohira, with whom the 1979 elections marked a good affirmation of the liberal democratic party, even if there was the loss of a seat.

Ohira, then, following the distrust he had in the government, called early elections but could not establish them definitively because he suddenly died. The task was taken by Z. Suzuki, but the two years of his rule were negative and then in October 1982 he was replaced by Y. Nakasone.

A man of lively personality, he identified himself with all the people of the neo-nationalist tendency. He was facilitated in his task first by the gradual withdrawal of the United States from East Asia, after the end of the Vietnam War, and then because, having been elected American President Ronald Reagan, there was a return everywhere to the moderate tones of the ‘ideology.

In domestic politics Nakasone was also favored by the decline of the oppositions. The Japanese Communist Party was greatly affected by the negative events between China and Vietnam regarding the Cambodian question. The socialist party, on the other hand, was constantly torn apart by opposing, moderate and radical internal currents.

A few years earlier, I. Asukata had reached the top of the Socialist party, who, while intending to represent the left, had left open the possibility of entry to other currents, even to the neo-Buddhists.

But on the eve of the general elections in late 1983, Asukata retired to give way to M. Ishibashi. Previously, the June elections, aimed at renewing a good half of the House of Councilors, had decreed a good result for the ruling party. The latter however were not very satisfactory, despite the high commitment made by Nakasone.

The liberal democrats could once again have an absolute majority only for the help of a group of independents and with that of a small group of liberal-autonomous.

The following year, despite these results, Nakasone was reconfirmed to lead the party. And this was at least surprising since for a time the conviction had developed that an alternation of parties in government would be more suitable for the progress of the country.

But the left all over the world had suffered a great decline and so the leaders of the Japanese economy had a very easy task. To help Nakasone in the government, without doubt, Tanaka contributed, who, although tried and convicted twice for corruption, always exercised a certain power over public opinion. He died of a brain hemorrhage in 1985.

The election results of 1986 were again in favor of the liberal democrats, while the socialists still registered a loss. And this caused Ishibashi’s resignation, who was replaced by a woman, Mrs. T. Doi, at the head of the party. Within the Tanaka stream, however, N. Takeshita dominated.

During the year 1986, the last government for Nakasone, the railways were privatized. In the autumn of 1987 Nakasone advocated the succession for Takeshita who, in fact, on 6 November became prime minister.

The first success was in the liberalization of agricultural products. And here, after a short time, another financial scandal broke out; many political leaders were accused of receiving bribes to facilitate the rise of the Recruit Cosmos. Takeshita was involved and resigned. The succession was extremely difficult. In the end, the choice fell on the foreign minister, S. Uno. He governed for a short time because in turn he was involved in another scandal. A woman publicly declared that she had been kept by him for many years and then unworthily abandoned. His resignation was the logical consequence.

Meanwhile, the liberal-democratic party in the supplementary elections of 23 July 1989 lost the majority. With the new general elections in August, Toshiri Kaifu, a member of the party’s smaller faction, became Prime Minister and Party President.

But in January 1989, Emperor Hirohito had disappeared after 62 years of reign. His successor was Crown Prince Akihito.

In June 1992, after bitter disputes, a law was passed which required the sending of Japanese soldiers abroad on peacekeeping missions, under the auspices of the United Nations.

In the late 1990s, the Japanese political and social model suffered a profound crisis. Too many bureaucratic impediments did not allow the various companies the right competitiveness with Western democracies. The transition from a bureaucratic state to a rule of law, from the sovereignty of the public administration to that of the citizens, was being asked from many quarters. In particular, young people, who grew up in the shadow of economic well-being and consumerism, disavowed traditional morality, increasingly linked to material pleasures.

And yet a serious economic recession had come. Moreover, a policy without alternation weakened the government and in the elections of July 1993 the liberal democratic party went into a minority. And the ruling coalition that took over the reins of power had M. Hasokawa as its representative. In 1994 he had to leave because he was accused of financial offenses.

After a very brief political period, led by T. Hata, the socialists entered into an alliance with the liberal democrats and after 47 years they returned to the government, headed by the social democrat T. Murayama.

In 1994, a new electoral law was passed which provided for the reduction of members of the House of Representatives and the introduction of the proportional, as well as limiting financial aid to parties.

The political situation was extremely unstable. In 1995, two famous television personalities won the election. In 1996 the Murayama government fell and the conservative Hashimoto was born, which was confirmed in 1996 and again in April 1997.

The following year, however, the leader of the major liberal-democratic faction, K. Obuchi, a traditional politician, was defeated and the government took office.

In 1999 the liberal party joined the government. And since it was evident that the well-being of the country would derive from cooperation and not from the opposition with China, which was in the same situation, the two countries have recently decided to achieve a parallel political legitimacy.